Introduction

When Connie Francis walked onto the set of Live with Regis and Kathie Lee in 1989, the audience expected nostalgia. What they got instead was resurrection.

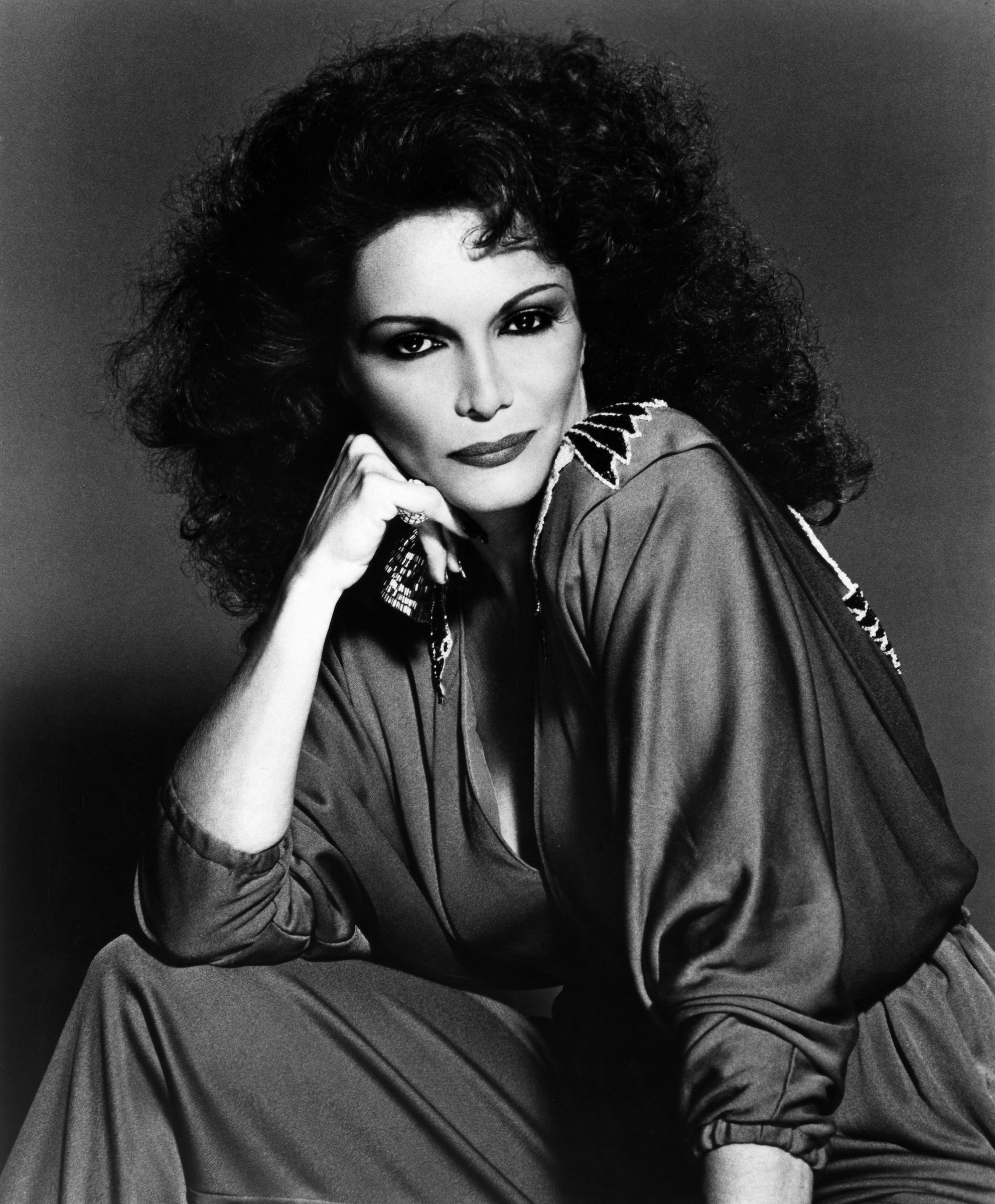

Her signature bouffant defied gravity; her smile, practiced yet fragile, carried the glint of a woman who had survived hell and somehow found her way back into the light. Hidden beneath her chic striped dress was a strip of medical tape—a small, almost invisible detail that told the story of pain endured and defiance reclaimed.

“Don’t worry,” she teased Regis Philbin as she crossed her bandaged foot. “I’ll think of something hot for the stage—maybe rhinestones and glitter!”

The studio erupted in laughter. It was classic Connie: turning pain into performance, tragedy into style.

But behind that laugh was the unspoken truth—the kind no amount of glamour could conceal. This was not just a comeback. It was an act of survival.

A Voice Silenced by Violence

For most of America, Connie Francis was the golden girl of the late ‘50s and ‘60s. Her songs—“Who’s Sorry Now?”, “Where the Boys Are”—defined a generation of innocence. Yet fame would become the stage for her deepest nightmares.

In 1974, while staying at a motel in Westbury, she was brutally assaulted—a trauma so devastating it robbed her of her voice and her will to sing. Years of therapy, silence, and lawsuits followed. Then came another heartbreak: in 1981, her beloved brother George was murdered in a mob-related attack.

For more than a decade, the world forgot the name Connie Francis. But she never forgot who she was.

The Return Nobody Saw Coming

Now, sitting across from Regis and Kathie Lee, she wasn’t just performing—she was reclaiming her story.

“When I lost everything,” she said quietly, eyes shimmering under studio lights, “I decided that if I couldn’t sing again, I’d at least tell the truth.”

That truth included the hardest confession of all.

“It’s called bipolar disorder,” she told the stunned hosts. “And it’s not about tragedy or circumstance—it’s a chemical imbalance in your brain.”

For 1989 daytime television, it was explosive. No pop idol, least of all one from the golden age of glamour, had ever spoken so candidly about mental illness. Francis’s voice didn’t tremble; it commanded.

“I refused to take medication at first,” she admitted. “‘I’m not going to be a drug addict. I’m not going to be a zombie.’ That’s what I told my doctor.”

Her psychiatrist, she recalled with a wry smile, didn’t flinch.

“Then buy a lot of stock in a mental hospital,” he told her bluntly, “because that’s where you’ll be spending the rest of your life.”

That, Francis said, “was the moment I decided to fight back.”

Laughter Through Tears

To watch her that morning was to witness both fragility and fire. The live audience didn’t just clap—they stood. They weren’t applauding a nostalgic star; they were saluting a survivor.

“Connie was fearless,” recalls longtime friend and disc jockey Cousin Brucie Morrow, who had known her since the days of sock hops and transistor radios. “I watched her walk through fire. The fact that she could sit there, crack jokes, and still sing after everything she went through—it was beyond brave. It was historic.”

Her new tour was already selling out twenty cities across the U.S., her voice stronger than it had been in years. A new album was in production, and Hollywood was buzzing over a rumored sequel to Where the Boys Are—cheekily titled “Where the Men Are.”

“It’s poetic, isn’t it?” she laughed. “After everything I’ve been through, I finally get to ask where the men are—and maybe this time, I’ll find the right one!”

It was that self-deprecating humor that endeared her to audiences for decades—a mix of grit and grace that made her more than a singer, but a symbol of what it means to keep standing.

Behind the Curtain

The cameras caught her smiling, but the pain was always near. Years of electroshock therapy, hospital stays, and battles with depression had taken their toll. Yet she refused to hide it.

“People see the makeup and the dresses,” she said in one interview that year. “They don’t see the mornings when you can’t get out of bed. I wanted to show that even a so-called ‘perfect’ star can break—and still come back.”

Her candidness broke new ground in a culture that often silenced women who struggled. It made her, in a strange and powerful way, more relatable than ever.

“Connie didn’t just sing about heartbreak,” said Dr. Richard Baer, her longtime physician. “She lived it. But she also lived the recovery—and that’s what makes her voice matter again. She reminds people that survival isn’t pretty, but it’s possible.”

A Legacy Rewritten

By the end of the interview, Regis’s teasing had softened into awe. Kathie Lee reached across to squeeze Connie’s hand.

“You’ve been through so much,” she said softly. “How do you still find the courage to laugh?”

Connie smiled.

“Because laughter was the only thing that ever made me feel like myself again.”

Outside the studio, fans who had grown up with her records wept openly. She had given them something rare—permission to be human.

In a decade obsessed with youth and perfection, Connie Francis had done the unthinkable: she had made vulnerability glamorous.

Her broken foot, wrapped in white tape, had become a badge of honor. Her scars—both visible and invisible—were no longer things to hide but proof of a war survived.

The Unbreakable Voice

Thirty years earlier, she had sung “Who’s Sorry Now?” to a world that adored her innocence. Now, she was the woman who could finally answer that question—not with bitterness, but with wisdom.

“I’ve been through every kind of heartbreak there is,” she said as the audience gave her a standing ovation. “But I’m still here. And I still have a song to sing.”

And with that, Connie Francis stood—her bandaged foot barely touching the ground—and began to hum the opening notes of “Where the Boys Are.”

The studio fell silent.

It wasn’t nostalgia anymore. It was rebirth.