Introduction

It was July 5, 1954, and the Memphis heat was brutal. Inside a cramped studio at 706 Union Avenue, a shy 19-year-old truck driver named Elvis Presley was about to quit his dream. He had spent hours trying—and failing—to record a tender love song called “I Love You Because.” His voice, smooth but stiff, just didn’t work. The room was filled with frustration. Sam Phillips, the head of Sun Records, looked deflated. Guitarist Scotty Moore leaned back, exhausted. Bassist Bill Black was tapping the floor, restless. Nothing clicked. Then, in one careless, magical moment, everything changed.

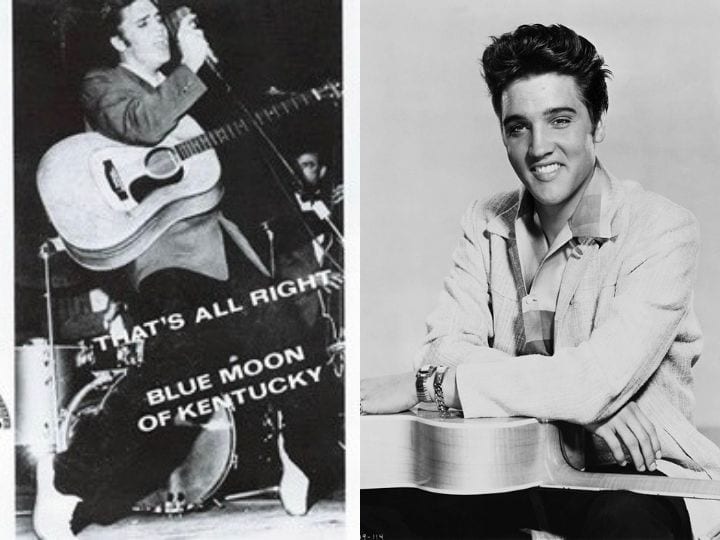

During a break, Elvis began fooling around. He grabbed his battered acoustic guitar, strummed a few quick chords, and burst into a wild, playful version of Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup’s “That’s All Right, Mama.” He wasn’t performing; he was just blowing off steam—laughing, stomping, singing faster, louder, looser. Bill jumped in, slapping his bass like a runaway train. Scotty followed with bright, twitchy guitar riffs. It was chaos—and it was alive.

From the control booth, Sam Phillips froze. Something electric cut through the heavy Memphis air. “What are you doing?” he shouted, bursting into the room. The musicians stopped, startled. “I don’t know,” Scotty mumbled. Phillips’ response became legend: “Whatever it is, do it again.”

That one command changed music forever.

The Birth of Fire

They played it again—and this time, Sam hit “Record.”

The tape rolled. Three minutes of pure lightning poured out. It wasn’t country, blues, or gospel—it was everything at once. The sound was raw, reckless, full of heart. “That’s All Right” didn’t belong to any genre; it invented one.

Scotty Moore later told Rolling Stone:

“Elvis just started cutting loose, jumping around, doing what came natural. It wasn’t planned. Bill and I just followed his lead. None of us knew we were making history—we were just having fun.”

Even Sam Phillips admitted in a 1979 interview:

“That was the moment I’d been waiting for. A white boy with the feel of a Black man’s rhythm—that mix of energy and soul. I knew, right then, this was it.”

From a Joke to a Revolution

Phillips quickly pressed an acetate copy and handed it to Dewey Phillips, Memphis’s most influential DJ (no relation). Dewey hesitated at first. It didn’t sound like anything he’d ever played on “Red, Hot and Blue.” But curiosity won. He spun the record that night—and the phone lines exploded. Call after call poured in:

“Who’s that?”

“Play it again!”

“Is he colored?”

Dewey played “That’s All Right” fourteen times in one night. When he finally called Elvis for a live interview, the terrified teenager was at home, hiding. His parents had to drive him to the station. The first thing Dewey asked on-air?

“Which high school did you go to, Elvis?”

The answer—Humes High, a white school—eased racial tension. The myth was set: a Southern boy with the voice of a man who’d walked through fire.

The Sound of Freedom

When Sun Records released “That’s All Right” two weeks later, Memphis went mad. Teenagers danced. Parents panicked. Churches warned of sin and danger. But something irreversible had begun. Those three minutes captured the exact moment America cracked open—the first tremor of rock and roll’s Big Bang.

The record wasn’t planned, polished, or approved. It was an accident—a joyful, spontaneous rebellion against failure. And that’s exactly why it worked. The sound said: Forget the rules. Feel the moment.

Elvis Presley, Scotty Moore, and Bill Black didn’t set out to make history. They just stopped trying to sound right—and started sounding real.

The Domino Effect

The next day, kids lined up outside record stores asking for “that new song by that Presley boy.” No one even knew how to spell his name. Within weeks, Elvis quit his job as a truck driver. By the end of the year, he was performing live across the South, hips shaking, voice trembling with gospel heat and rock fury.

“That’s All Right” had only sold a few thousand copies—but its impact was nuclear. Country stations banned it. R&B DJs embraced it. And in every diner, car radio, and juke joint, a new sound echoed—wild, free, untamed.

Music historian Peter Guralnick once said:

“What happened that night wasn’t invention—it was discovery. The discovery of what happens when instinct meets courage.”

That instinct, that refusal to quit, became Elvis’s blueprint. His early recordings at Sun—“Blue Moon of Kentucky,” “Good Rockin’ Tonight,” “Mystery Train”—all carried that same spark: simple, unfiltered joy colliding with something darker and deeper.

The Lost Heat of 706 Union Avenue

Decades later, if you walk into Sun Studio, you can still feel it—the air, thick with history, the faint smell of tube amps and sweat. The same tiles still echo. The same walls that caught those first notes of “That’s All Right” now shimmer like a shrine. Musicians from all over the world come there to chase that ghost.

Phillips once said, “I didn’t invent rock and roll. I just caught it before it flew away.” And that’s exactly what happened on that July night. The song wasn’t written—it escaped.

Three Minutes That Changed the World

When you strip away the myth, “That’s All Right” is just a song about letting go. But inside its rhythm lies the DNA of every musical rebellion that followed—The Beatles, Dylan, The Stones, Springsteen. Every snarl, every guitar riff, every cry for freedom traces back to those three minutes.

Bill Black never lived long enough to see the legend fully bloom. Scotty Moore, humble until his last days, always insisted Elvis deserved the credit. But anyone who’s ever picked up a guitar knows the truth: rock and roll was born when three men stopped caring what it was supposed to be.

The Echo Still Burns

In the summer of 1954, no one thought a sweaty kid from Tupelo could change the world. Yet, as Sam Phillips hit “Record,” a new era began—unpolished, dangerous, alive. It was the sound of rebellion wearing blue suede shoes.

And maybe, just maybe, the real miracle wasn’t the song itself. It was that moment when a young man who thought he had failed chose to sing one more time.

(To be continued: how “That’s All Right” transformed Sun Studio into ground zero for an entire cultural explosion—and how the world’s first rock record lit the fuse for a movement that never stopped burning.)