Introduction

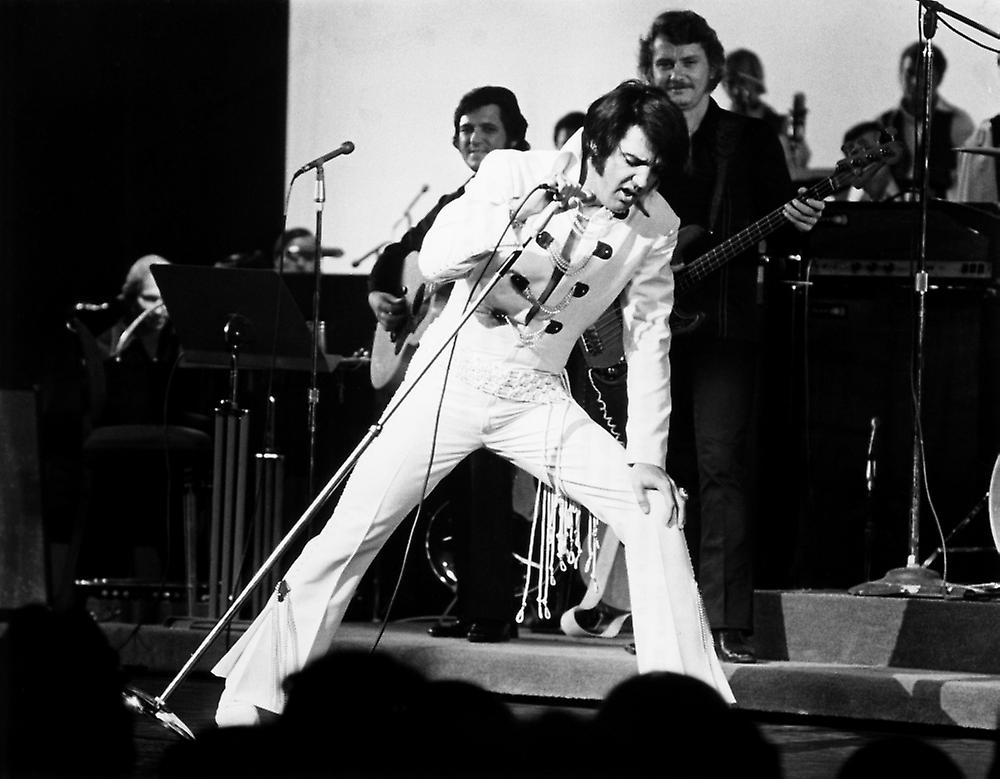

Las Vegas, 1970. The desert air shimmered, the spotlight burned white-hot, and Elvis Presley, draped in his diamond-studded jumpsuit, looked every inch the King of Rock and Roll. But when the first notes of “Polk Salad Annie” thundered through the International Hotel, something shifted. The King wasn’t just performing — he was possessed.

“Some of y’all don’t know much about the South,” Elvis said with that half-smile, sweat glinting on his brow. “Lemme tell y’all a little story so you’ll understand what I’m talkin’ about.”

Then it happened. The stage lights dimmed, the room fell silent, and a growling rhythm from Jerry Scheff’s bass began pulsing like the heartbeat of the Mississippi delta. In that instant, Elvis wasn’t the Vegas showman anymore. He was the Tupelo boy — barefoot, proud, wild — tearing down the glittering illusion and bringing the swamp to the Strip.

The Rebirth of a King

By 1970, Elvis had become a monument — untouchable, adored, but almost trapped inside his own legend. The jumpsuits, the screaming crowds, the Vegas empire — it was all a gilded cage. Yet “Polk Salad Annie”, a swamp-rock anthem written by Tony Joe White, cracked the marble mask wide open.

White later confessed in a 1973 interview, “He owned it. When Elvis sang ‘Polk Salad Annie,’ it wasn’t my song anymore. It was him. He looked like he was back in the dirt, fightin’ for every note.”

The original track was about a poor Southern girl scraping by on what the swamp gave her — polk salad, a wild green known only to those who’d grown up hungry. For Elvis, it wasn’t fiction. It was his mother Gladys’s voice, his childhood poverty in Tupelo, his roots clawing their way through the rhinestones.

A Storm on Stage

As the horns blared and the TCB Band locked in, Elvis transformed. His body became a whirlwind — karate kicks slicing through the air, his voice rasping, growling, preaching. This wasn’t choreography. It was possession.

Audience member and Vegas regular Linda Thompson later recalled: “You could feel the air change. It wasn’t Elvis the star — it was Elvis the spirit. You didn’t watch him; you felt him.”

Each movement was primal. Each snarl a confession. He didn’t just sing “Polk Salad Annie”; he lived it again, channeling the ghosts of the South through every muscle and bead of sweat.

Behind him, the TCB Band tried to keep up — Ronnie Tutt’s drums pounding like thunder, James Burton’s guitar snapping like a whip. The brass section stoked the fire until the crowd erupted.

A Reminder of Where He Came From

Those who knew Elvis best said that “Polk Salad Annie” was his secret weapon — his way of grounding himself when the Vegas mirage got too bright. His lifelong friend Jerry Schilling explained:

“When Elvis was offstage, sometimes he’d get restless, sad even. But when he sang ‘Polk Salad Annie,’ it was like he came alive again. He needed that connection to where he came from — to the dirt, the sweat, the struggle.”

Every performance of the song became a kind of ritual — a reminder that no matter how many diamonds adorned his collar, Elvis Presley’s power didn’t come from Las Vegas. It came from the South.

Tony Joe White’s Southern Spell

“Polk Salad Annie” had been born in Louisiana mud. Tony Joe White’s original version — raw, funky, and dripping with swamp heat — was a sleeper hit in 1969. But when Elvis picked it up, it exploded.

“He called me up after hearing it,” White once said with a grin. “He told me, ‘Man, that song’s got grit.’ I knew right then he understood it. Elvis was that song.”

That “grit” — the hunger, danger, and Southern swagger — bled through every second of Elvis’s performance. Fans screamed. Critics stood in awe. For once, the show wasn’t about perfection. It was about truth.

When the King Became Mortal Again

The final minutes of “Polk Salad Annie” were chaos — pure, glorious chaos. Elvis, drenched in sweat, hair wild, shirt half-open, hit his last move like a man exorcising something deep inside him. Then — silence.

Flashbulbs went off. The audience gasped. In that moment, he wasn’t The King. He was Elvis Aaron Presley from Tupelo, the boy who’d clawed his way out of the red dirt to stand under the hottest lights on earth.

Photographer Ed Bonja, who shot hundreds of Elvis shows, once said:

“That song scared me — in a good way. You could see something ancient take over him. It wasn’t Vegas. It was the South. It was his soul.”

The Song That Saved His Fire

After 1970, “Polk Salad Annie” became a staple in his setlist. No matter how grand the venue or how exhausted he was, that song always pulled something raw and human out of him. It was his rebellion against becoming a caricature.

Every “uhh!” grunt, every thrust, every slap of the mic stand screamed the same message: “I’m still here.”

And maybe that’s why those who saw it never forgot. Because, beneath the rhinestones, beneath the legend, there was still the same Southern boy — the same heartbeat that shook the world in 1956 — trying to break free again.

In Las Vegas, 1970, Elvis didn’t just perform “Polk Salad Annie.”

He reclaimed himself.

And as Jerry Schilling once put it:

“That night, Elvis wasn’t the King of Vegas. He was the King of the Swamp. And God help anyone who tried to follow him after that.”

(To be continued: Inside the rehearsals — how “Polk Salad Annie” nearly broke the TCB Band and why Elvis said it was the only song that ever made him “feel alive again.”)